This afternoon I dropped a 30-page sample RFP document into Claude Code and typed: "Create an agent team to prepare clarification questions from different angles."

What happened next was genuinely promising. Four AI agents spawned in the terminal — a Solution Architect, a Commercial Lead, a Bid Manager, and an Engagement Lead. They divided the document among themselves, worked in parallel, and produced clarification questions I hadn't thought of. The Bid Manager caught a pass/fail criterion buried in page 27 that the others missed. The Commercial Lead flagged an ambiguous penalty clause that could have cost real money.

It felt less like using a tool and more like chairing a meeting. That's either exciting or terrifying, depending on how you think about where AI is heading.

What Agent Teams Actually Are

Anthropic shipped agent teams as part of Claude Code alongside the Opus 4.6 release on February 5th, 2026. The feature is experimental — disabled by default, hidden behind an environment variable. But the concept is significant enough to warrant attention.

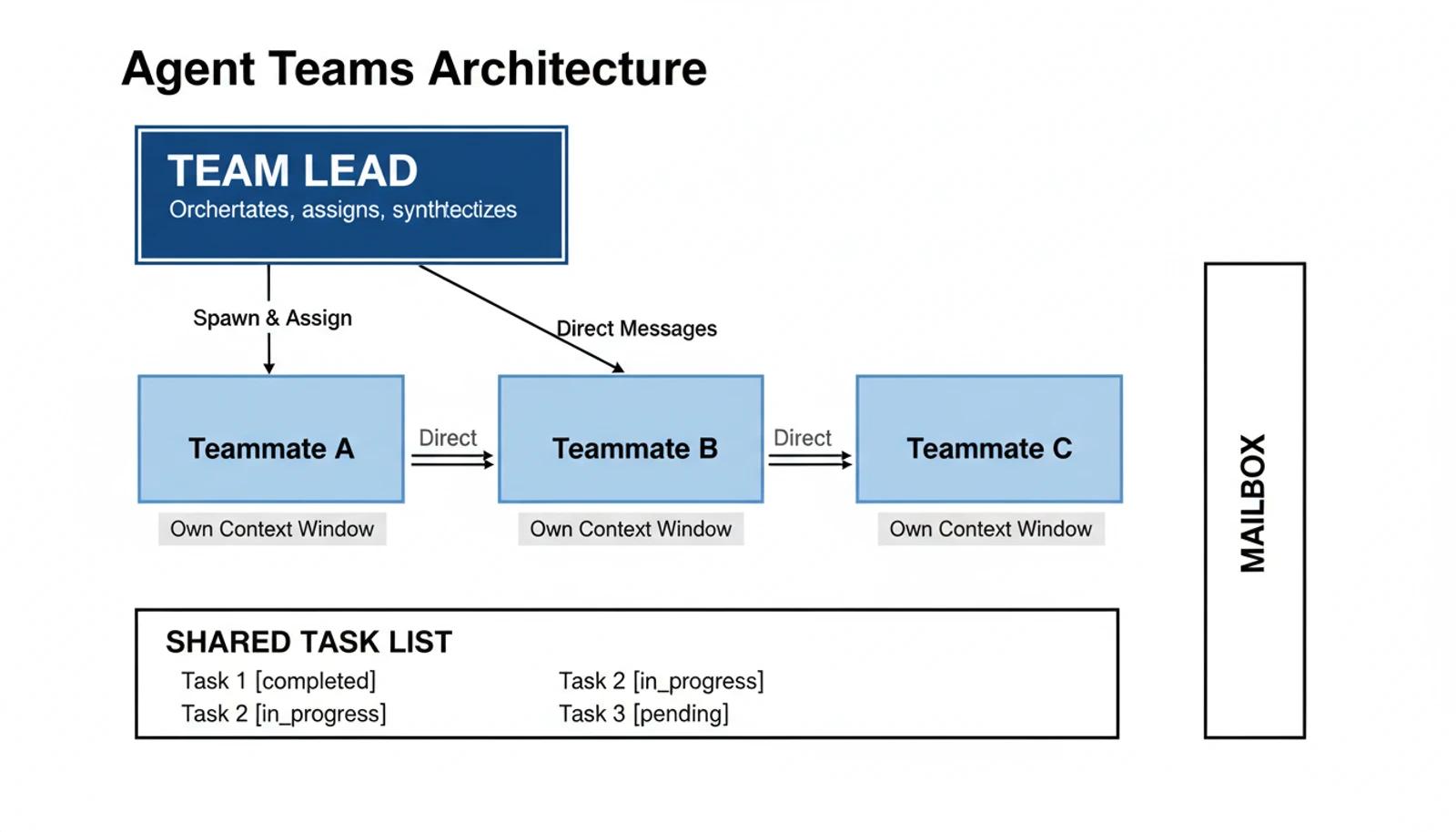

Here's the architecture:

| Component | Role |

|---|---|

| Team Lead | The main Claude Code session — creates the team, assigns tasks, synthesizes results |

| Teammates | Separate Claude Code instances, each with its own context window |

| Task List | Shared work tracker with dependency management and auto-unblocking |

| Mailbox | Direct agent-to-agent messaging — not just reporting back to the lead |

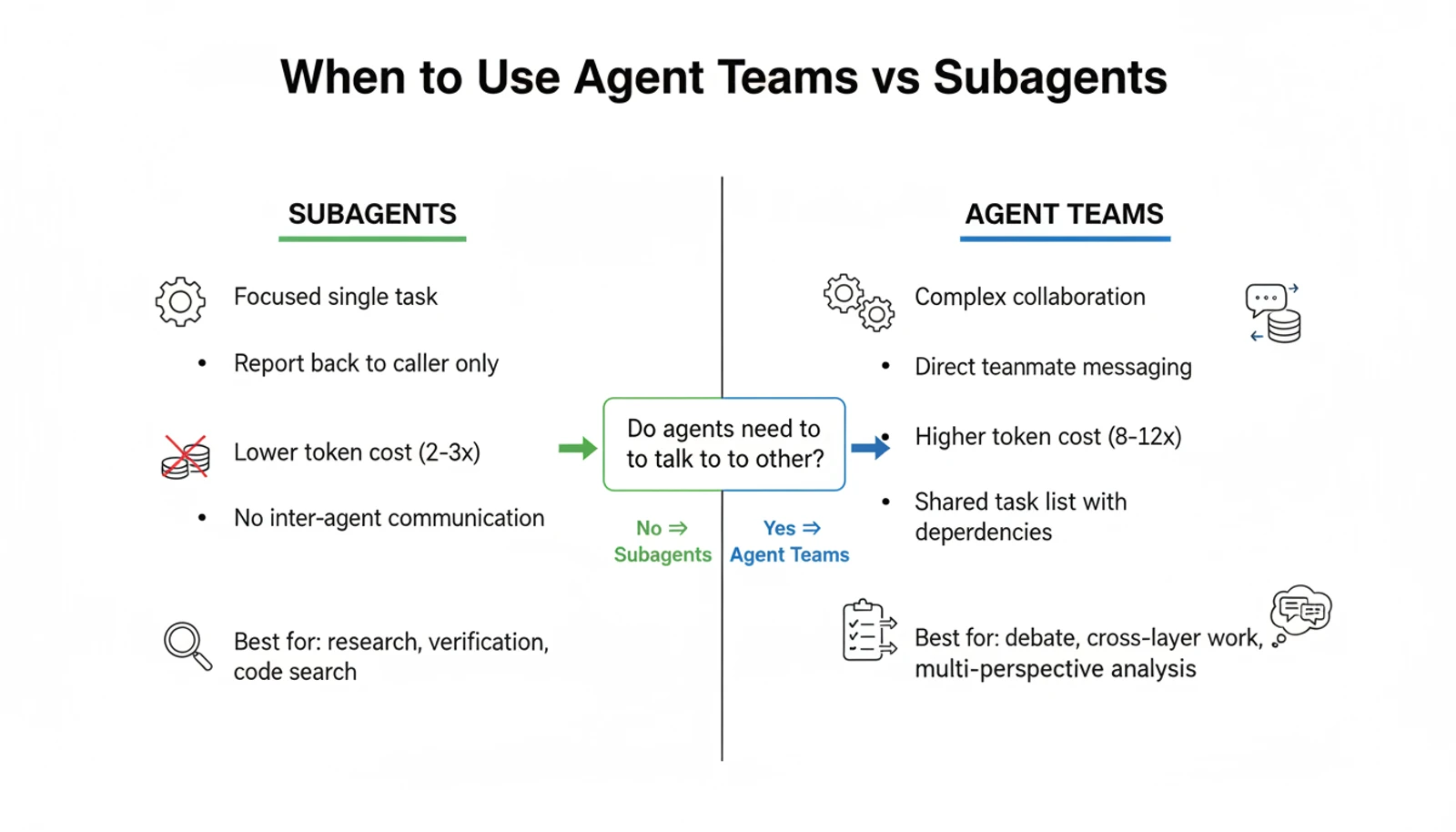

That last point is what makes this different from subagents, which Claude Code already had. Subagents are workers — they go out, do a job, and report back. Agent teams are collaborators. Teammates can message each other directly, challenge findings, and self-coordinate through the shared task list.

Think of it as the difference between delegating tasks to freelancers versus assembling a project team. The freelancer model is cheaper and simpler. The team model produces richer output — but it costs more and requires coordination overhead.

The Opus 4.6 Engine Behind It

Agent teams run on Opus 4.6, which shipped the same day. The model improvements aren't just incremental — they're what make multi-agent coordination feasible:

| Benchmark | Opus 4.5 | Opus 4.6 | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Context Window | 200K tokens | 1M tokens | Each teammate can hold vastly more project context |

| Terminal-Bench 2.0 | 59.8% | 65.4% | Better at agentic, multi-step coding tasks |

| MRCR v2 (long-context) | 18.5% | 76.0% | Retrieves information accurately across huge contexts |

| ARC AGI 2 | 37.6% | 68.8% | Novel problem-solving — critical for autonomous agents |

| OSWorld | 66.3% | 72.7% | Computer use capabilities for agentic workflows |

| SWE-bench Verified | 80.9% | 80.8% | Coding held steady — optimization went elsewhere |

The 1M token context window is particularly relevant for agent teams. Each teammate loads full project context — CLAUDE.md files, MCP servers, skills — when spawned. With a 200K limit, complex projects would have teammates working with partial information. At 1M tokens, each agent can see the full picture of a large codebase.

The jump from 18.5% to 76% on long-context retrieval (MRCR v2) is almost hard to believe. But it directly explains why agent teams work at all — each teammate needs to find relevant information within its massive context window without losing track of what it's doing.

My First Test: The RFP That Organized Itself

I didn't plan to test agent teams on an RFP. I was looking at the feature documentation, had an example RFP template sitting on my desk, and thought — why not.

The setup was one sentence:

Create an agent team to analyze this RFP and prepare clarification questions

from different professional angles.Claude proposed four teammates:

| Role | Agent Name | Focus Area |

|---|---|---|

| Solution Architect | solution-architect | Technical scope, architecture, deliverables |

| Commercial/Pricing Lead | commercial-lead | Pricing structure, contract terms, commercial risk |

| Bid Manager/Compliance | bid-manager | Evaluation criteria, submission format, pass/fail |

| Engagement/Delivery Lead | engagement-lead | Stakeholder engagement, logistics, methodology |

I watched them work in my terminal. Using Shift+Up/Down I could jump between agents to see their progress. The Solution Architect was methodically going through technical requirements. The Commercial Lead was already three sections ahead, flagging pricing ambiguities.

The results were comprehensive. Each agent produced 8–12 targeted questions from their domain. The Bid Manager found compliance requirements that could disqualify a submission if missed. The Engagement Lead identified a vague stakeholder definition that would cause problems during delivery.

What surprised me most: the questions had almost no overlap. Each agent genuinely focused on its assigned lens without drifting into territory belonging to another.

Why This Works (and When It Doesn't)

Agent teams aren't magic. They're an architectural pattern — and like all patterns, they have a sweet spot.

Where agent teams shine:

- Multi-perspective analysis — different lenses on the same material, like my RFP test

- Parallel code review — one agent on security, another on performance, a third on test coverage

- Competing hypothesis debugging — three agents investigating three possible root causes simultaneously

- Cross-layer implementation — frontend, backend, and tests each owned by a different agent

Where they don't make sense:

- Sequential tasks — if step 2 depends on step 1's output, parallelism adds nothing

- Same-file edits — two agents editing the same file causes overwrites

- Simple tasks — coordination overhead exceeds the benefit for anything a single session handles fine

The Anthropic engineering team stress-tested this aggressively. They had 16 agents collaboratively build a Rust-based C compiler from scratch — 100,000 lines of code across nearly 2,000 sessions, costing $20,000 in API usage. The compiler can build Linux 6.9 on x86, ARM, and RISC-V, pass 99% of GCC torture tests, and boot Linux to run Doom.

That project surfaced real lessons about coordination at scale:

"Claude will work autonomously to solve whatever problem I give it. So it's important that the task verifier is nearly perfect, otherwise Claude will solve the wrong problem."

They used a bare Git repository mounted across Docker containers, with simple file-based locking to prevent task conflicts. When agents faced monolithic problems, they stalled — the fix was using GCC as a comparison oracle to isolate bugs to specific files, enabling parallel debugging.

The Cost Reality

Here's what nobody talks about enough: agent teams are expensive.

My RFP analysis with four teammates consumed roughly 14% of a single session's context budget. Each teammate is a full Claude instance with its own context window. Token usage scales linearly with team size.

| Approach | Relative Token Cost | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Single session (Opus) | 1x | Most tasks |

| 4 subagents (Sonnet) | ~2–3x | Parallel research, focused tasks |

| 4-agent team (all Opus) | ~8–12x | Complex collaboration with cross-talk |

| 4-agent team (Sonnet + Opus lead) | ~3–5x | Best cost/quality balance |

The practical optimization: use Sonnet for teammates and Opus for the lead only. Sonnet handles focused, well-scoped tasks effectively. The lead — which does orchestration, synthesis, and judgment calls — benefits from Opus-level reasoning. This cuts costs by roughly 60% without meaningful quality loss.

Other cost-saving patterns:

- Cap deliverables: "Output a numbered list of max 10 questions" prevents agents from endlessly exploring

- Use delegate mode (

Shift+Tab): prevents the lead from duplicating work that teammates are already doing - Size tasks at 5–6 per teammate: too small and coordination overhead dominates; too large and agents run without check-ins

For many parallel tasks, subagents are actually the better choice. They run a focused turn, return results, and terminate — no ongoing context windows, no mailbox overhead. The rule of thumb: use agent teams only when teammates genuinely need to talk to each other. Most parallel tasks don't.

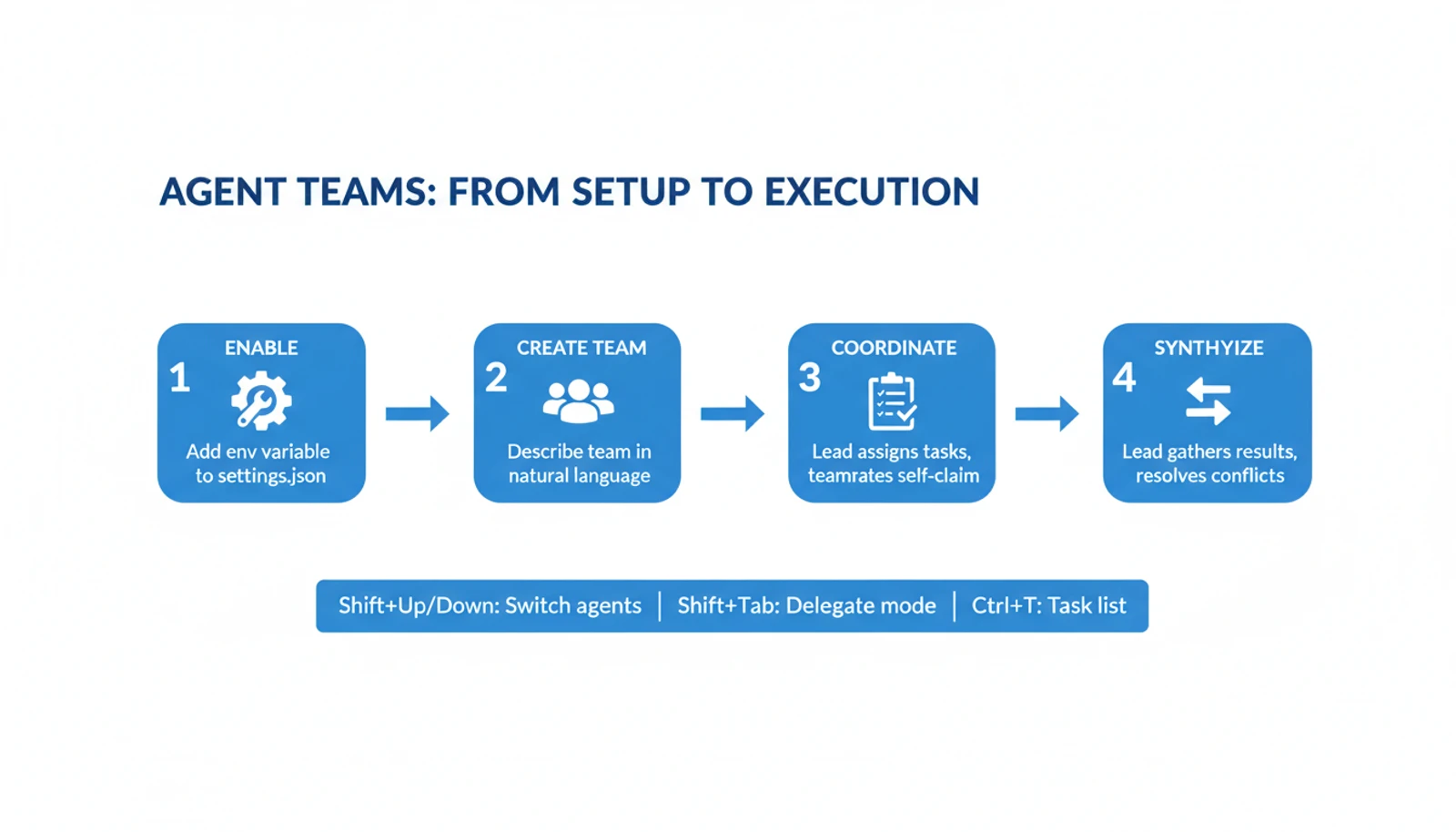

Setting It Up

Agent teams are disabled by default. Enable them by adding one line to your settings:

In ~/.claude/settings.json:

{

"env": {

"CLAUDE_CODE_EXPERIMENTAL_AGENT_TEAMS": "1"

}

}Then restart Claude Code and describe the team you want in natural language:

Create a team with 3 teammates to refactor the authentication module.

One teammate on the backend changes, one on frontend updates,

one writing tests. Use Sonnet for teammates.Key controls:

| Action | How |

|---|---|

| Switch between agents | Shift+Up/Down |

| Toggle delegate mode | Shift+Tab |

| View task list | Ctrl+T |

| Interrupt a teammate | Enter to view, then Escape |

| Split pane mode | claude --teammate-mode tmux (requires tmux) |

Require plan approval for risky tasks — teammates work read-only until the lead approves their approach:

Spawn an architect teammate to redesign the database layer.

Require plan approval before any changes.

What I Learned

After running agent teams on real work, a few patterns became clear.

Context is everything. Teammates don't inherit the lead's conversation history. They get project context (CLAUDE.md, MCP servers, skills) and the spawn prompt — nothing else. A vague spawn prompt produces vague work. The more specific you are about files, focus areas, and expected deliverables, the better the output.

It feels like managing a team. The dynamics are uncannily similar to real team coordination. You need to define clear ownership. You need to size work appropriately. You need to check in on progress and redirect agents that go off-track. You need to prevent two people from editing the same file. These are management problems translated into AI orchestration.

The debate pattern is underrated. My favorite use case isn't parallel implementation — it's adversarial research. Spawn five agents with competing hypotheses, tell them to try to disprove each other, and let the surviving theory win. Single-agent investigation suffers from anchoring bias; multi-agent debate breaks it.

Start with read-only tasks. If you're new to agent teams, try review and research tasks first — analyzing a PR, investigating a bug, preparing documentation. These have clear boundaries and don't require the coordination discipline that parallel implementation demands.

The Bigger Picture

Agent teams are experimental. The current limitations are real — no session resumption, task status can lag, no nested teams, one team per session. Anthropic marks this as a research preview, and it shows in the rough edges.

But the direction is unmistakable. We've gone from single AI completions to multi-turn conversations to autonomous agents to coordinated agent teams — in about three years. The C compiler project — 16 agents, 100,000 lines of working code — is a proof of concept for a future where AI teams tackle projects that would take human teams months.

The question isn't whether this will become reliable. It's whether we're ready to think about AI as something we manage rather than something we use.

I'm not sure I am. But after watching four agents dissect an RFP better than most teams I've worked with — I'm paying attention.