Yesterday I wrote about how skills are replacing workflow nodes as the building blocks of AI-powered automation. The concept is clean: package domain expertise into composable capabilities, let an intelligent agent orchestrate them, and watch rigid IFTTT graphs give way to adaptive, judgment-rich workflows.

The response surfaced a question I'd been circling myself: what exactly is open-sourced here? Is it the specification? The implementation? Both? And if I want to build a skills-powered system for my own use case — not just consume Anthropic's — what code exists for reference, and what do I write from scratch?

The answer, it turns out, has three layers. And a follow-up question that's equally important: if every major tool now supports skills, does each one have its own runtime? The answer is yes — and understanding who built what tells you everything about what's easy, what's possible, and where the real engineering work lives.

The Three-Layer Landscape

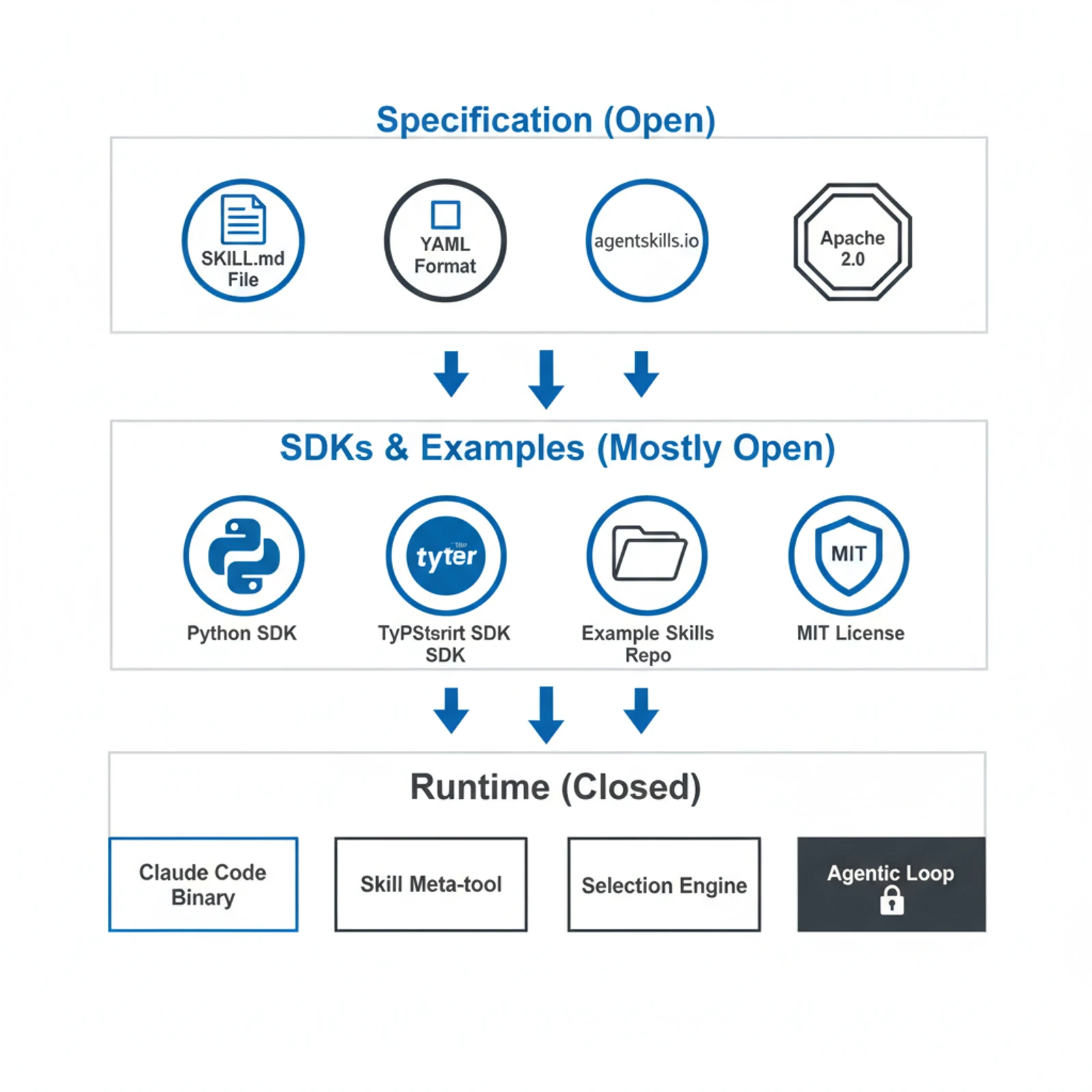

The Agent Skills ecosystem splits into three distinct layers, each with different open-source status:

| Layer | What It Is | Open? | Where |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specification | The SKILL.md format, directory structure, naming rules | Fully open (Apache 2.0 + CC-BY-4.0) | agentskills.io |

| SDKs & Examples | Agent SDKs, example skills, validation tools | Mostly open (MIT / Apache 2.0) | GitHub repos |

| Runtime | The engine that discovers, selects, loads, and orchestrates skills | Varies by vendor | Each tool built their own |

This is a deliberate architecture — and it mirrors how web standards work. Anthropic open-sourced the format (like HTML), released SDKs and examples, and built their own runtime (like Chrome). But just as Firefox and Safari implement the same HTML spec with their own engines, every major AI tool that supports skills has built its own runtime too.

If this sounds familiar, it's the same playbook Anthropic used with MCP. Open the protocol. Let the ecosystem build connectors. The standard is portable even if individual implementations are proprietary. MCP now has over 97 million monthly SDK downloads and 10,000+ active servers. The strategy works — and skills are following the same trajectory.

Layer 1: The Specification — What the Spec Actually Defines

The Agent Skills spec, maintained at github.com/agentskills/agentskills and published at agentskills.io, defines the format — nothing more, nothing less.

A skill is a directory containing a SKILL.md file with YAML frontmatter:

---

name: pdf-processing

description: Extract text and tables from PDF files, fill PDF forms, merge documents. Use when working with PDF documents.

license: Apache-2.0

metadata:

author: example-org

version: "1.0"

---The spec is precise about naming constraints (lowercase, hyphens only, 1–64 characters, no consecutive hyphens) and description requirements (1–1024 characters, should describe both what and when). Optional fields include license, compatibility (environment requirements), metadata (arbitrary key-value pairs), and an experimental allowed-tools field for pre-approved tool permissions.

Beyond the single file, the spec defines optional directories:

my-skill/

├── SKILL.md # Required: instructions + metadata

├── scripts/ # Optional: executable code

├── references/ # Optional: supplementary docs

└── assets/ # Optional: templates, schemas, imagesThe most important design decision in the spec is progressive disclosure. The spec explicitly recommends a three-tier information loading strategy:

- Metadata (~100 tokens): name and description loaded at startup for all skills

- Instructions (under 5000 tokens recommended): full SKILL.md body loaded on activation

- Resources (as needed): scripts, references, assets loaded only when required

This isn't just a suggestion — it's the architectural pattern that makes skills scale. Without progressive disclosure, an agent with 50 installed skills would burn its entire context window on instructions it might never need. The spec keeps SKILL.md under 500 lines and pushes detail into separate files.

The agentskills repo also ships a skills-ref validation library (Python) so you can verify your skills conform to the spec before deployment.

Layer 2: The SDKs — What Code You Actually Get

Anthropic provides two official paths for working with skills in code:

The Claude Agent SDK (Python, TypeScript) — MIT licensed — bundles the Claude Code CLI and provides a programmatic interface for building applications that use skills. Configuration is straightforward:

from claude_agent_sdk import query, ClaudeAgentOptions

options = ClaudeAgentOptions(

cwd="/path/to/project", # Must contain .claude/skills/

setting_sources=["user", "project"], # Required for skill discovery

allowed_tools=["Skill", "Read", "Write", "Bash"],

)

async for message in query(

prompt="Help me process this PDF document",

options=options,

):

print(message)There's a critical subtlety here. Setting allowed_tools=["Skill"] alone does nothing — you must also configure setting_sources to tell the SDK where to look for skills on the filesystem. This trips up many developers.

The SDK handles skill discovery and loading for you, but with an important limitation: skills must be filesystem artifacts. There's no programmatic API for registering skills at runtime. You can't dynamically create a skill in memory and inject it into the system. Everything flows through SKILL.md files on disk.

The Example Skills repo (github.com/anthropics/skills) — 71k+ stars — contains production-quality skills for document processing (PDF, DOCX, XLSX, PPTX), creative applications, and enterprise workflows. Most are Apache 2.0; the document creation skills are source-available (you can read and learn from them, but the license restricts redistribution). These serve as excellent reference implementations for skill design, even if you're not using Claude.

What the SDKs don't give you is the runtime engine. The SDK wraps the Claude Code CLI binary, which is where the actual skill orchestration happens. If you want skills to work with a different LLM or in a completely custom system, the SDK won't help — you need to build the runtime yourself.

Layer 3: The Runtime — What It Actually Does

Here's where it gets interesting. Every skills-capable tool needs a runtime that performs six core functions. The specific implementations differ — Claude Code's is closed source, OpenClaw's is fully readable — but the pattern is consistent across all of them. Understanding these functions is essential whether you're evaluating existing tools or building your own.

1. Skill Discovery

At startup, the runtime scans configured directories for SKILL.md files and parses the YAML frontmatter. The result is a registry of skill metadata: names, descriptions, and file locations. Every implementation does this the same way — it's just filesystem traversal plus YAML parsing. The only differences are which directories each tool scans and whether they support hot-reload (OpenClaw does, via file watching with configurable debounce).

2. Skill Selection (Where Implementations Diverge)

This is where tools make meaningfully different design choices.

Claude Code uses a pure LLM-based approach: it formats all available skill names and descriptions into an <available_skills> XML block embedded in a meta-tool's dynamic prompt. When a user makes a request, Claude's language model reads this formatted list and reasons about which skill is relevant. No embeddings, no classifiers, no regex. Selection quality scales with model capability, not routing logic.

OpenClaw takes a more active approach: selective injection filtered by tool policy and per-turn relevance. Instead of showing all skill descriptions to the LLM every turn, it pre-filters to include only contextually appropriate skills. This avoids burning tokens on irrelevant descriptions when only a few skills matter.

Codex and Copilot land somewhere in between — they use progressive disclosure (metadata at startup, full content on activation) but let the model drive selection based on description matching.

3. Skill Loading

When the agent decides to invoke a skill, the runtime reads the full SKILL.md content and injects it into the conversation context. Claude Code uses a dual-message architecture — one visible message indicating activation, one hidden message containing the full instructions. Other tools inject the skill content directly into the system prompt or a dedicated prompt section. The goal is the same: get the instructions into the LLM's context without cluttering the user interface.

4. Context Modification

The loaded skill can modify the execution environment — injecting pre-approved tool permissions, overriding model selection, or adjusting token allocation. In Claude Code, a contextModifier function handles this, scoped to the skill's execution. OpenClaw manages this through its skills.entries[name] configuration with per-skill API keys, environment variables, and tool policy bindings. The details differ but the principle is universal: skills can change what the agent is allowed to do.

5. Progressive Resource Loading

As the skill executes, it may reference additional files (scripts, reference docs, assets). The runtime loads these on demand, keeping context usage proportional to actual need. This is the third tier of the spec's progressive disclosure pattern.

6. The Agentic Loop

The orchestration loop continues until the goal is met or iteration limits are exceeded. At each step, the agent reasons about results, decides next actions, and may load additional resources. Each tool result becomes part of the conversation history, maintaining full context. OpenClaw delegates this to Pi Agent Core; Claude Code handles it in its proprietary binary; Microsoft's reference implementation runs a simple while-loop that continues until the LLM responds without tool calls.

The Runtime Landscape: Who Built What

Here's the question that tripped me up initially: if the runtime is "closed source inside Claude Code," does that mean only Claude supports skills? Not at all. Every major AI coding tool has implemented its own runtime — the spec is open, and the runtime pattern is well-understood enough that multiple teams built it independently.

| Tool | Runtime Status | Skill Directories | Selection Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Claude Code | Proprietary (closed binary) | .claude/skills/, ~/.claude/skills/ | LLM-based, all descriptions in Skill tool prompt |

| OpenAI Codex | Proprietary (built natively) | .agents/skills/, ~/.agents/skills/, /etc/codex/skills/ | Progressive disclosure, explicit (/skills) + implicit |

| VS Code Copilot | Proprietary (built natively) | .github/skills/, .claude/skills/, .agents/skills/ | Frontmatter description matching, auto + manual |

| Windsurf | Proprietary (via Cascade) | .windsurf/skills/, ~/.codeium/windsurf/skills/ | Per-turn relevance filtering |

| OpenClaw | Open source | workspace/skills/, ~/.openclaw/skills/, configurable | Selective injection with tool policy filtering |

Notice the pattern: every vendor scans different directories but implements the same six-component architecture. They all parse SKILL.md with YAML frontmatter, maintain a metadata registry, and inject skill instructions into the LLM context when relevant. The spec standardizes the format; each runtime standardizes the experience within its own ecosystem.

The most interesting entry is OpenClaw. As the only major tool with a fully open-source codebase, it's where you go to read actual runtime code rather than infer behavior from documentation. Their skills implementation lives in src/agents/system-prompt.ts (prompt assembly with skill injection) and src/agents/piembeddedrunner.ts (the agentic loop), with Pi Agent Core handling the underlying LLM interaction and tool execution.

As discussed in the runtime components above, OpenClaw's selective injection approach contrasts with Claude Code's "show everything, let the model choose" strategy. Their configuration system (openclaw.json under skills.*) also supports per-skill API keys, environment variables, and enable/disable toggles — enterprise-grade controls that are visible in the source code for anyone to study or adapt.

The practical implication: if you use any of these tools, you already have a skills runtime. You don't need to build one. A SKILL.md file written to the spec works across all of them.

Where it gets interesting is when you step outside these ecosystems — building a custom agent on raw LLM APIs, or integrating skills into an existing application. That's where reference implementations come in.

Reference Implementations: Open Code You Can Study

If you're building a custom agent or want to understand how the runtime works at a code level, three open implementations are worth studying — each taking a fundamentally different approach.

OpenClaw (Full Production Runtime — Open Source)

OpenClaw is the strongest reference available — 148k stars, 5,700+ skills on its ClawHub marketplace, and a fully readable codebase. The skills architecture is covered in detail in the runtime landscape section above. If you want to understand how a production skills runtime works at a code level, start here.

Microsoft's .NET Skills Executor (Reference Architecture)

Microsoft published a clean reference implementation that wires Agent Skills to Azure OpenAI with MCP tool access. Four components: Skill Loader (YAML parsing), Azure OpenAI Service (LLM interaction), MCP Client Service (tool access), and Skill Executor (agentic loop).

The key design decision: zero business logic in the orchestrator. The executor provides available tools to the LLM, executes requested calls, and feeds results back. All intelligence comes from the skill's instructions combined with the LLM's reasoning. If you want a minimal, principled architecture to adapt to your own stack, this is the template.

OpenSkills (Universal Adapter)

OpenSkills takes a different approach entirely. Instead of building a full runtime, it acts as a compatibility layer. It scans installed skills, generates an <available_skills> metadata block in AGENTS.md format, and provides a CLI command (npx openskills read <skill-name>) for on-demand skill loading.

This works with any AI coding agent that reads AGENTS.md — Cursor, Windsurf, Aider, Codex, and others. It's not a runtime so much as a bridge that makes SKILL.md files portable across agents that don't natively support them yet.

Roll Your Own (The Minimal Path)

If you're building from scratch and none of the above fit your needs, the minimal viable skills runtime needs four pieces:

1. Parse SKILL.md → YAML parser + markdown reader

2. Build skill registry → HashMap<name, metadata>

3. Format for your LLM → Inject skill list into system prompt

4. Load on activation → Read full SKILL.md when LLM selects a skillThe selection mechanism is the most important design decision. You have two options:

| Approach | How It Works | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| LLM-based (Claude's approach) | Include all skill descriptions in prompt, let the model choose | Zero code, scales with model quality | Uses tokens, dependent on model reasoning |

| Algorithmic | Embedding similarity, keyword matching, or classifier | Deterministic, fast, cheap | Requires training data, brittle to novel inputs |

For most applications, the LLM-based approach is simpler and more robust. You're already paying for model inference — letting the model read a few hundred tokens of skill descriptions costs almost nothing.

The Decision Framework: What Should You Actually Do?

This depends on where you're building:

| Scenario | Recommendation | Runtime Situation |

|---|---|---|

| Using Claude Code or Agent SDK | Just write skills | Runtime is bundled. You're done. |

| Using OpenAI Codex | Just write skills | Codex has native skills support. |

| Using VS Code Copilot | Just write skills | Copilot scans .github/skills/ natively. |

| Using Windsurf | Just write skills | Cascade handles skills natively. |

| Using OpenClaw | Just write skills | Full runtime included, plus ClawHub marketplace. |

| Using Cursor or other agents | Install OpenSkills | Bridges SKILL.md to any AGENTS.md-compatible agent. |

| Building a custom agent on any LLM | Study OpenClaw's source, adapt | Fork their pattern or reference Microsoft's .NET impl. |

| Just writing skills, tool-agnostic | Follow the spec, ignore runtime | Skills are portable across all implementations. |

The key insight: for most developers, the runtime question is already solved. If you're using any mainstream AI coding tool, skills work out of the box. You only need to think about building a runtime if you're creating a custom agent from scratch — and even then, OpenClaw's open-source codebase and Microsoft's reference architecture give you a substantial head start.

The spec is designed so that skills written once work everywhere. A SKILL.md file created for Claude Code works in Codex, Copilot, Windsurf, OpenClaw, Cursor (via OpenSkills), in a custom .NET application (via Microsoft's executor), or in any future runtime that implements the spec. This portability is the real value of the open standard.

Implementation Best Practices

From studying the reference implementations and building my own skills workflows, these patterns hold up:

1. Keep the orchestrator dumb. The Microsoft implementation nails this. The executor has zero business logic — it provides tools, runs LLM calls, and feeds results back. All intelligence comes from the skill instructions plus the model's reasoning. The moment you start adding routing logic to the orchestrator, you're fighting the model instead of leveraging it.

2. Progressive disclosure is not optional. Even with large context windows, loading every skill's full instructions at startup is wasteful. Load metadata (~100 tokens per skill) at startup, full instructions on activation, and resources on demand. The spec recommends this, and every successful implementation follows it.

3. Version skills in git. Treat skills like code — because they are code. Version them, review changes, test before deploying. The skills-ref validation library catches format issues, but you still need to verify that skills produce correct behavior.

4. Design for the agentic loop, not single-shot. Skills aren't functions that return a value. They're multi-step workflows where the agent reasons about intermediate results. Write skills that define success criteria, not just action sequences. The agent should know when it's done, not just what steps to follow.

5. Test selection, not just execution. The most common failure mode isn't a broken skill — it's a skill that never gets invoked. Test that your description triggers correctly across different phrasings of the same intent. If your skill doesn't activate when it should, the description needs work, not the instructions.

6. Separate MCP tools from skill logic. MCP servers provide raw capabilities (read a database, call an API). Skills provide the workflow logic (when to query, how to interpret results, what to do next). Mixing them creates skills that only work with specific MCP configurations. Keep them independent.

Where This Is Headed

The runtime question is largely settled. Claude Code, Codex, Copilot, Windsurf, and OpenClaw all have production-grade skills runtimes. The competitive differentiation is shifting from "can your tool run skills?" to "how well does it select and orchestrate them?" — which is ultimately a model quality question, not an infrastructure question.

The more interesting trajectory is in the skills themselves. OpenClaw's ClawHub marketplace already hosts 5,700+ community skills. OpenAI launched their own skills catalog for Codex. Anthropic's example repo has 71k stars. Skills are becoming a new category of shared infrastructure — like npm packages or Docker images, but for AI agent capabilities. The supply chain security implications are real (OpenClaw has already dealt with malicious skills), but the ecosystem is growing faster than the guardrails.

For builders, the practical advice is straightforward: if you're using any mainstream AI tool, skills just work — focus your energy on writing good skills rather than building runtime infrastructure. If you're building a custom agent, start by reading OpenClaw's source code — it's the most complete open-source reference available. And regardless of which tool you use, write skills against the open spec. The format is the durable investment. The runtime is the implementation detail that's already been solved six different ways.

Sources:

- Agent Skills Specification — agentskills.io

- Agent Skills Repository — GitHub

- Agent Skills Standard Specification — GitHub

- Claude Agent SDK (Python) — GitHub

- Claude Agent SDK (TypeScript) — GitHub

- Agent Skills in the SDK — Claude Platform Docs

- Claude Agent Skills: A First Principles Deep Dive — Lee Han Chung

- OpenClaw Repository — GitHub

- OpenClaw Skills System Architecture — DeepWiki

- OpenClaw Architecture Overview — Paolo Perazzo

- Agent Skills for Codex — OpenAI Developers

- Use Agent Skills in VS Code — VS Code Docs

- Cascade Skills — Windsurf Docs

- Building an AI Skills Executor in .NET — Microsoft Foundry Blog

- OpenSkills: Universal Skills Loader — GitHub

- Anthropic Launches Skills Open Standard — AI Business

- Agent Skills: Anthropic's Next Bid to Define AI Standards — The New Stack